Introduction

-

- Human (Articulated) Body Pose Estimation:

- Human Pose Estimation is the process of estimating the configuration of the body (pose) from a single, typically monocular, image.

- In computer vision, Body Pose Estimation is the study of algorithms and systems that recover the pose of an articulated body, which consists of joints and rigid parts using image-based observations.

-

- Difficulties in Pose Estimation:

- Pose estimation is hard due to many reasons including:

- High Degree of Freedom (DOF): 244 DOF

- Variability of human visual appearance

- Variability in lighting conditions

- Variability in human physique

- (partial) Occlusions

- Complexity of the human physical structure

- high dimensionality of the pose

- loss of 3d information that results from observing the pose from 2d planar image projections

- (variability in) Clothes

-

- Theory:

- Human pose estimation is usually formulated Probabilistically to account for the variability and ambiguities that exist in the inference.

- In Probabilistic approaches, we are interested in estimating the posterior distribution \(p(\mathbf{x}\vert \mathbf{z})\), where \(\mathbf{x}\) is the pose of the body and and \(\mathbf{z}\) is a feature set derived from the image.

-

- The Key Modeling choices that affect the inference are:

- The representation of the pose – \(\mathbf{x}\)

- The nature and encoding of image features – \(\mathbf{z}\)

- The inference framework required to estimate the posterior – \(p(\mathbf{x}\vert \mathbf{z})\)

- The Key Modeling choices that affect the inference are:

- Further Reading

-

- Model-based Approaches:

- The typical body pose estimation system involves a model-based approach, in which the pose estimation is achieved by maximizing/minimizing a similarity/dissimilarity between an observation (input) and a template model.

- Different kinds of sensors have been explored for use in making the observation.

- Sensors:

- Visible wavelength imagery

- Long-wave thermal infrared imagery

- Time-of-flight imagery

- Laser range scanner imagery

- Sensors:

- These sensors produce intermediate representations that are directly used by the model.

- Representations:

- Image appearance

- Voxel (volume element) reconstruction

- 3D point clouds, and sum of Gaussian kernels

- 3D surface meshes.

- Representations:

-

- The Representation:

- A Representation is a model to depict the configuration of the human body.

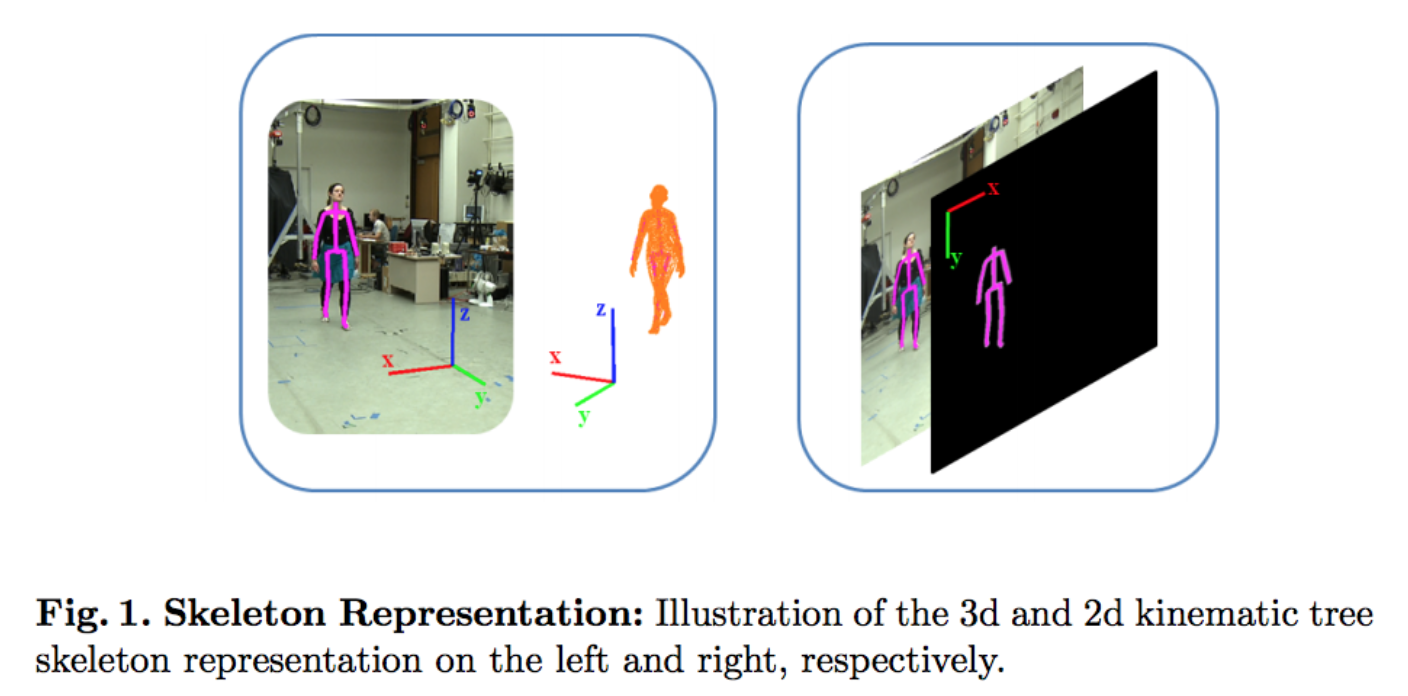

The configuration of the human body can be represented in a variety of ways. - There are two common representations used for the human body:

- Kinematic Skeleton Tree

- Part Models

-

- Kinematic Skeleton Tree with Quaternions:

- The most direct and common representation is obtained by parameterizing the body as a kinematic tree, \(\vec{x} = \{\tau, \theta_\tau, \theta_1, \theta_2, \ldots, \theta_N\}\), where the pose is encoded using position of the root segment (the pelvis is typically used as root to minimize the height of the kinematic tree), \(\tau\), orientation of the root segment in the world, \(\theta_\tau\), and a set of relative joint angels, \(\{\theta_i\}_{i=1}^N\), that represent the orientation of the body parts with respect to their parents along the tree.

e.g., the orientation of the thigh with respect to the pelvis, shin with respect to the thigh, etc.

- The kinematic skeleton is constructed by a tree-structured chain where each rigid body segment has its local coordinate system that can be transformed to the world coordinate system via a 4×4 transformation matrix \({\displaystyle T_{l}}\),

- \[{\displaystyle T_{l}=T_{\operatorname {par} (l)}R_{l},}\]

- where \({\displaystyle R_{l}}\) denotes the local transformation from body segment \({\displaystyle S_{l}}\) to its parent \({\displaystyle \operatorname {par} (S_{l})}\).

- Kinematic tree representation can be obtained for 2d, 2.5d, and 3d body models.

- 2-D:

- \(\tau \in \mathcal{R}^2\),

- \(\theta_\tau \in \mathcal{R}^1\),

- \(\theta_i \in \mathcal{R}^1\): corresponds to pose of the cardboard person in the image plane

- 3-D:

- \(\tau \in \mathcal{R}^3\),

- \(\theta_\tau \in SO(3)\),

- \(\theta_i \in SO(3)\): for spherical joints, e.g. neck

\(\theta_i \in \mathcal{R}^2\): for saddle joints, e.g. wrist

\(\theta_i \in \mathbb{R}^1\): for hinge joints, e.g. knee

- 2.5-D: are extensions of the 2-D representations where the pose, \(\mathbf{x}\), is augmented with (discrete) variables encoding the relative depth (layering) of body parts with respect to one another in the 2-d cardboard model.

This representation is not very common.

- 2-D:

- Each joint in the body has 3 degrees of freedom (DoF) rotation. Given a transformation matrix \({\displaystyle T_{l}}\), the joint position at the T-pose can be transferred to its corresponding position in the world coordination.

The 3-D joint rotation is, usually, expressed as a normalized quaternion \([x, y, z, w]\) due to its continuity that can facilitate gradient-based optimization in the parameters estimation. - In all (dimensionality) cases, kinematic tree representation results in a high-dimensional pose vector, \(\mathbf{x}\), in \(\mathbb{R}^{30} - \mathbb{R}^{70}\), depending on the fidelity and exact parameterization of the skeleton and joints.

- Another parameterization uses the (2d or 3d) locations of the major joints in the world.

However, this parametrization is not invariant to the morphology (body segment lengths) of a given individual.

-

- Part-based Models:

- The body is modeled as a set of parts, \(\mathbf{x} = \{\mathbf{x}_1, \mathbf{x}_2, \ldots, \mathbf{x}_M\}\), each with its own position and orientation in space, \(\mathbf{x}_i = \{\tau_i, \theta_i\}\), that are connected by a set of statistical or physical constraints that enforce skeletal (and sometimes image) consistency.

- The part model is motivated by the human skeleton, since any object having the property of articulation can be broken down into smaller parts wherein each part can take different orientations, resulting in different articulations of the same object.

Different scales and orientations of the main object can be articulated to scales and orientations of the corresponding parts. - Mathematically, the parts are connected by springs; the model is, also, known as a spring model.

The degree of closeness between each part is accounted for by the compression and expansion of the springs. There is geometric constraint on the orientation of springs. For example, limbs of legs cannot move 360 degrees. Hence parts cannot have that extreme orientation. This reduces the possible permutations. - The model can be formulated in 2-D or in 3-D.

The 2-D parameterizations are much more common.

In 2-D, each part’s representation is often augmented with an additional variable, \(s_i\), that accounts for uniform scaling of the body part in the image, i.e., \(\mathbf{x}_i = \{\tau_i, \theta_i, s_i\}\) with \(\tau_i \in \mathbb{R}^2, \theta_i \in \mathbb{R}^1\) and \(s_i \in \mathbb{R}^1\). - The model results in very high dimensional vectors, even higher than that of kinematic trees.

-

- Applications:

-

- Markerless motion capture for human-computer interfaces,

- Physiotherapy

- 3D animation

- Ergonomics studies

- Robot control and

- Visual surveillance

- Human-robot interaction

- Gaming

- Sports performance analysis

-

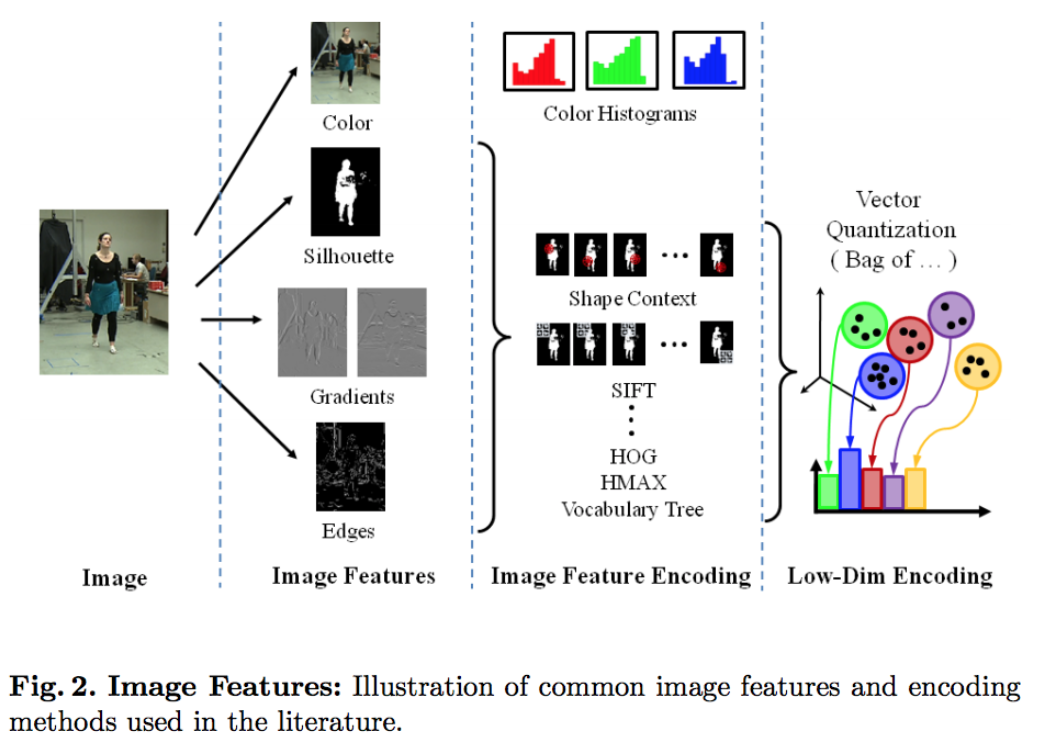

- Image Features:

- In many of the classical approaches image features that represent the salient parts of the image with respect to the human pose play a huge rule in the performance of any pose estimation approach.

-

- The most common features:

- Silhouettes: for effectively separating the person from background in static scenes

- Color: for modeling un-occluded skin or clothing

- Edges: for modeling external and internal contours of the body

- Gradients: for modeling the texture over the body parts

Other, less common features, include, Shading and Focus.

- The most common features:

- To reduce dimensionality and increase robustness to noise, these raw features are often encapsulated in image descriptors, such as shape context, SIFT, and histogram of oriented gradients (HoG).

Alternatively, hierarchical multi-level image encodings can be used, such as HMAX, spatial pyramids, and vocabulary trees.

***

DeepPose

-

- Main Idea:

- Pose Estimation is formulated as a DNN-based regression problem towards body joints.

The DNN regressors are presented as a cascade for higher precision in pose estimates.

-

- Structure:

-

- Input:

- Full Image

- 7-layered generic Convolutional DNN

Each Joint Regressor uses the full image as a signal.

- Input:

-

- Key Insights:

-

- Replace the explicitly designed feature representations and detectors for the parts, the model topology, and the interactions between joints by a learned representation through a ConvNet

- The (DNN-based) Pose Predictors are presented as a cascade to increase the precision of joint localization

- Although the regression loss does not model explicit interactions between joints, such are implicitly captured by all of the 7 hidden layers – all the internal features are shared by all joint regressors

-

- Method:

-

- Start with an initial pose estimation (based on the full image)

- Learn DNN-based regressors which refine the joint predictions by using higher resolution sub-images

-

- Notation:

-

- Pose Vector = \(\mathbf{y} = \left(\ldots, \mathbf{y}_i^T, \ldots\right)^T, \: i \in \{1, \ldots, k\}\)

- Joint Co-ordinates = \(\mathbf{y}_i^T = (x_i, y_i)\) of the \(i\)-th joint

- Labeled Image = \((x, \mathbf{y})\)

- \(x =\) Image Data

- \(\mathbf{y} =\) Ground-Truth Pose Vector

- Bounding Box = \(b\): a box bounding the human body or parts of it

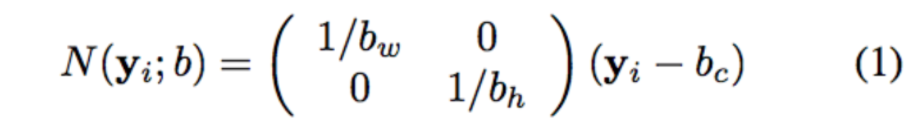

- Normalization Function \(= N(\mathbf{y}_i; b)\): normalizes the joint coordinates w.r.t a bounding box \(b\)

Since the joint coordinates are in absolute image coordinates, and poses vary in size from image to image

- Translate by box center

- Scale by box size

- Normalized pose vector = \(N(\mathbf{y}; b) = \left(\ldots, N(\mathbf{y}_i; b)^T, \ldots\right)^T\)

- A crop of image \(x\) by bounding box \(b\) = \(N(x; b)\)

- Learned Function = \(\psi(x;\theta) \in \mathbb{R}^2k\) is a functions that regresses to normalized pose vector, given an image:

- Input: image \(x\)

- Output: Normalized pose vector \(N(\mathbf{y})\)

-

- Pose Prediction:

- \[y^\ast = N^{-1}(\psi(N(x);\theta))\]

-

- Architecture:

-

- Problem: Regression Problem

- Goal: Learn a function \(\psi(x;\theta)\) that is trained and used to regress to a pose vector.

- Estimation: \(\psi\) is based on (learned through) Deep Neural Net

- Deep Neural Net: is a Convolutional Neural Network; namely, AlexNet

- Input: image with pre-defined size \(= \:\) #-pixels \(\times 3\)-color channels

\((220 \times 220)\) with a stride of \(4\)

- Output: target value of the regression\(= 2k\) joint coordinates

- Input: image with pre-defined size \(= \:\) #-pixels \(\times 3\)-color channels

-

Denote by \(\mathbf{C}\) a convolutional layer, by \(\mathbf{LRN}\) a local response normalization layer, \(\mathbf{P}\) a pooling layer and by \(\mathbf{F}\) a fully connected layer

-

For \(\mathbf{C}\) layers, the size is defined as width \(\times\) height \(\times\) depth, where the first two dimensions have a spatial meaning while the depth defines the number of filters.

-

- Alex-Net:

- Architecture: \(\mathbf{C}(55 \times 55 \times 96) − \mathbf{LRN} − \mathbf{P} − \mathbf{C}(27 \times 27 \times 256) − \mathbf{LRN} − \mathbf{P} − \\\mathbf{C}(13 \times 13 \times 384) − \mathbf{C}(13 \times 13 \times 384) − \mathbf{C}(13 \times 13 \times 256) − \mathbf{P} − \mathbf{F}(4096) − \mathbf{F}(4096)\)

- Filters:

- \(\mathbf{C}_{1} = 11 \times 11\),

- \(\mathbf{C}_{2} = 5 \times 5\),

- \(\mathbf{C}_{3-5} = 3 \times 3\).

- Total Number of Parameters \(= 40\)M

- Training Dataset:

Denote by \(D\) the training set and \(D_N\) the normalized training set:

\(\ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \\) \(\ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \\) \(D_N = \{(N(x),N(\mathbf{y}))\vert (x,\mathbf{y}) \in D\}\) - Loss: the Loss is modified; instead of a classification loss, we train a linear regression on top of the last network layer to predict a pose vector by minimizing \(L_2\) distance between the prediction and the true pose vector,

- Alex-Net:

- \[\arg \min_\theta \sum_{(x,y) \in D_N} \sum_{i=1}^k \|\mathbf{y}_i - \psi_i(x;\theta)\|_2^2\]

-

- Optimization:

- BackPropagation in a distributed online implementation

- Adaptive Gradient Updates

- Learning Rate \(= 0.0005 = 5\times 10^{-4}\)

- Data Augmentation: randomly translated image crops, left/right flips

- DropOut Regularization for the \(\mathbf{F}\) layers \(= 0.6\)

- Optimization:

-

- Architecture:

-

- Motivation:

Although, the pose formulation of the DNN has the advantage that the joint estimation is based on the full image and thus relies on context, due its fixed input size of \(220 \times 220\), the network has limited capacity to look at detail - it learns filters capturing pose properties at coarse scale.

The pose properties are necessary to estimate rough pose but insufficient to always precisely localize the body joints.

Increasing the input size is infeasible since it will increase the already large number of parameters.

Thus, a cascade of pose regressors is used to achieve better precision. - Structure and Training:

At the first stage:- The cascade starts off by estimating an initial pose as outlined in the previous section.

At subsequent stages: - Additional DNN regressors are trained to predict a displacement of the joint locations from previous stage to the true location.

Thus, each subsequent stage can be thought of as a refinement of the currently predicted pose.

- Each subsequent stage uses the predicted joint locations to focus on the relevant parts of the image – subimages are cropped around the predicted joint location from previous stage and the pose displacement regressor for this joint is applied on this sub-image.

Thus, subsequent pose regressors see higher resolution images and thus learn features for finer scales which ultimately leads to higher precision

- The cascade starts off by estimating an initial pose as outlined in the previous section.

- Method and Architecture:

- The same network architecture is used for all stages of the cascade but learn different parameters.

- Start with a bounding box \(b^0\): which either encloses the full image or is obtained by a person detector

- Obtain an initial pose:

Stage 1: \(\mathbf{y}^1 \leftarrow N^{-1}(\psi(N(x;b^0);\theta_1);b^0)\) - At stages \(s \geq 2\), for all joints:

- Regress first towards a refinement displacement \(\mathbf{y}_i^s - \mathbf{y}_i^{(s-1)}\) by applying a regressor on the sub image defined by \(b_i^{(s-1)}\)

- Estimate new joint boxes \(b_i^s\):

Stage \(s\): \(\ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \mathbf{y}_i^s \leftarrow \mathbf{y}_i^{(2-1)} + N^{-1}(\psi(N(x;b^0);\theta_s);b) \:\: (6) \\ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \:\:\:\: \text{for } b = b_i^(s-1) \\ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ b_i^s \leftarrow (\mathbf{y}_i^s, \sigma diam(\mathbf{y}^s), \sigma diam(\mathbf{y}^s))) \:\: (7)\)

where we considered a joint bounding box \(b_i\) capturing the sub-image around \(\mathbf{y}_i: b_i(\mathbf{y}; \sigma) = (\mathbf{y}_i, \sigma diam(\mathbf{y}), \sigma diam(\mathbf{y}))\) having as center the i-th joint and as dimension the pose diameter scaled by \(\sigma\), to refine a given joint location \(\mathbf{y}_i\).

- Apply the cascade for a fixed number of stages \(= S\)

- Loss: (at each stage \(s\))

- Motivation:

- \[\theta_s = \arg \min_\theta \sum_{(x,\mathbf{y}_i) \in D_A^s} \|\mathbf{y}_i - \psi_i(x;\theta)\|_2^2 \:\:\:\:\: (8)\]

-

- Advantages:

-

- The DNN is capable of capturing the full context of each body joint

- The approach is simpler to formulate than graphical-models methods - no need to explicitly design feature representations and detectors for parts or to explicitly design a model topology and interactions between joints.

Instead a generic ConvNet learns these representations

-

- Notes:

-

- The use of a generic DNN architecture is motivated by its outstanding results on both classification and localization problems and translates well to pose estimation

- Such a model is a truly holistic one — the final joint location estimate is based on a complex nonlinear transformation of the full image

- The use of a DNN obviates the need to design a domain specific pose model

- Although the regression loss does not model explicit interactions between joints, such are implicitly captured by all of the 7 hidden layers – all the internal features are shared by all joint regressors