Table of Contents

Resources:

- Regularization in FFN

- Regularization Concept

- Regularization Ch.7 Summary

- How Regularization Reduces Variance from bias-var-decomp

- Probabilistic Interpretation of Regularization (MAP)

- The Math of Regularization

- Regularization from excess risk

- Bayesian Interpretation of Regularization (wikipedia)

- Regularization Methods Papers Explained

- Improving Model Generalization (book)

- Regularization and Reproducing Kernel Hilbert Spaces (ESL)

Regularization Basics and Definitions

-

Regularization:

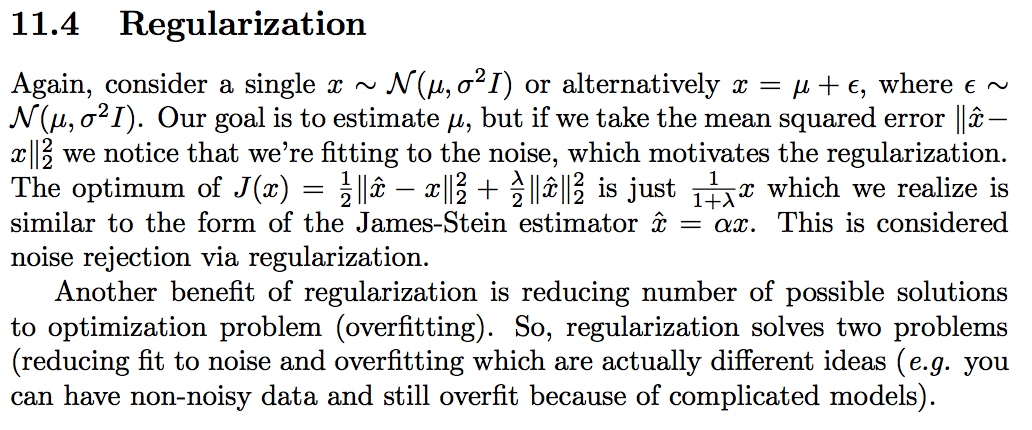

Regularization can be, loosely, defined as: any modification we make to a learning algorithm that is intended to reduce its generalization error but not its training error.Formally, it is a set of techniques that impose certain restrictions on the hypothesis space (by adding information) in order to solve an ill-posed problem or to prevent overfitting.1

-

Theoretical Justification for Regularization:

A theoretical justification for regularization is that it attempts to impose Occam’s razor on the solution.

From a Bayesian point of view, many regularization techniques correspond to imposing certain prior distributions on model parameters.Regularization from the NFL Theorem(s):

- The No Free Lunch Theorem:

The following statement is FALSE:

“Given a number of points (and a confidence), we can always achieve a prescribed error.” - Interpretation: inference from finite samples can be effectively performed if and only if the problem satisfies some a priori condition.

- Implications:

- This implies that there is no silver bullet: we shouldn’t expect any single optimization method to be perfect for all problems. Rather, we should try to design optimization methods that are tailored to the problem we’re trying to solve.

e.g. if you want to use local search, you’ll probably need to define a neighborhood relation that is informed by the problem domain. - A practical implication is that machine learning won’t work if there is no structure at all on the space of possible models/hypotheses.

Instead, we need some kind of prior that makes some models more likely than others.

- This implies that there is no silver bullet: we shouldn’t expect any single optimization method to be perfect for all problems. Rather, we should try to design optimization methods that are tailored to the problem we’re trying to solve.

- Implying Regularization:

One of the most used priors is Occam’s Razor which assumes that “simpler” models are more likely than complex one’s.

This leads to use of regularization in machine learning, as it effectively applies Occam’s razor to candidate models.2 - Summary: NFL Theorem shows that regularization strategies are necessary to obtain good generalization.

- Ref

Notes:

- Regularization emerges in a probabilistic (Bayesian) framework, where regularization can be performed by selecting a larger prior probability over simpler models; but also in statistical learning theory, where the goal is to minimize over two quantities: the ‘empirical risk’ and the ‘structural risk’, which roughly corresponds to the error over the training set and the predicted error in unseen data due to overfitting. - wikipedia

- The No Free Lunch Theorem:

-

Regularization in Deep Learning:

In the context of DL, most regularization strategies are based on regularizing estimators, which usually works by trading increased bias for reduced variance.An effective regularizer is one that makes a profitable trade, reducing variance significantly while not overly increasing the bias.

-

Regularization and Data Domains in DL - A Practical Motivation:

Most applications of DL are to domains where the true data-generating process is almost certainly outside the model family (hypothesis space). Deep learning algorithms are typically applied to extremely complicated domains such as images, audio sequences and text, for which the true generation process essentially involves simulating the entire universe.Thus, controlling the complexity of the model is not a simple matter of finding the model of the right size, with the right number of parameters; instead, the best fitting model (wrt. generalization error) is a large model that has been regularized appropriately.

Parameter Norm Penalties

- Parameter Norms:

Many regularization approaches are based on limiting the capacity of models by adding a parameter norm penalty \(\Omega(\boldsymbol{\theta})\) to the objective function \(J\). We denote the regularized objective function by \(\tilde{J}\):$$\tilde{J}(\boldsymbol{\theta} ; \boldsymbol{X}, \boldsymbol{y})=J(\boldsymbol{\theta} ; \boldsymbol{X}, \boldsymbol{y})+\alpha \Omega(\boldsymbol{\theta}) \tag{7.1}$$

where \(\alpha \in[0, \infty)\) is a HP that weights the relative contribution of the norm penalty term, \(\Omega\), relative to the standard objective function \(J\).

- Effects of \(\alpha\):

- \(\alpha = 0\) results in NO regularization

- Larger values of \(\alpha\) correspond to MORE regularization

The effect of minimizing the regularized objective function is that it will decrease, both, the original objective \(J\) on the training data and some measure of the size of the parameters \(\boldsymbol{\theta}\).

Different choices for the parameter norm \(\Omega\) can result in different solutions being preferred.

- Effects of \(\alpha\):

-

Parameter Penalties and the Bias parameter:

In NN, we usually penalize only the weights of the affine transformation at each layer and we leave the biases unregularized.

Biases typically require less data than the weights to fit accurately. The reason is that each weight specifies how TWO variables interact so fitting the weights well, requires observing both variables in a variety of conditions. However, each bias controls only a single variable, thus, we don’t induce too much variance by leaving the biases unregularized. If anything, regularizing the bias can introduce a significant amount of underfitting.

-

Note on the \(\alpha\) parameter for different hidden layers:

In the context of neural networks, it is sometimes desirable to use a separate penalty with a different \(\alpha\) coefficient for each layer of the network. Because it can be expensive to search for the correct value of multiple hyperparameters, it is still reasonable to use the same weight decay at all layers just to reduce the size of search space.

- \(L^2\) Parameter Regularization (Weight Decay):

It is a regularization strategy that drives the weights closer to the origin3 by adding a regularization term:$$\Omega(\mathbf{\theta}) = \frac{1}{2}\|\boldsymbol{w}\|_ {2}^{2}$$

to the objective function.

In statistics, \(L^2\) regularization is also known as Ridge Regression or Tikhonov Regularization.

Analyzing Weight Decay:

- What happens in a Single Step:

We can gain some insight into the behavior of weight decay regularization by studying the gradient of the regularized objective function.

Take the models objective function:$$\tilde{J}(\boldsymbol{w} ; \boldsymbol{X}, \boldsymbol{y})=\frac{\alpha}{2} \boldsymbol{w}^{\top} \boldsymbol{w}+J(\boldsymbol{w} ; \boldsymbol{X}, \boldsymbol{y}) \tag{7.2}$$

with the corresponding parameter gradient:

$$\nabla_{\boldsymbol{w}} \tilde{J}(\boldsymbol{w} ; \boldsymbol{X}, \boldsymbol{y})=\alpha \boldsymbol{w}+\nabla_{\boldsymbol{w}} J(\boldsymbol{w} ; \boldsymbol{X}, \boldsymbol{y}) \tag{7.3}$$

The gradient descent update:

$$\boldsymbol{w} \leftarrow \boldsymbol{w}-\epsilon\left(\alpha \boldsymbol{w}+\nabla_{\boldsymbol{w}} J(\boldsymbol{w} ; \boldsymbol{X}, \boldsymbol{y})\right) \tag{7.4}$$

Equivalently:

$$\boldsymbol{w} \leftarrow(1-\epsilon \alpha) \boldsymbol{w}-\epsilon \nabla_{\boldsymbol{w}} J(\boldsymbol{w} ; \boldsymbol{X}, \boldsymbol{y}) \tag{7.5}$$

Observe that the addition of the weight decay term has modified the learning rule to multiplicatively shrink the weight vector by a constant factor on each step, just before performing the usual gradient update.

- What happens over the Entire course of training:

We simplify the analysis by making a quadratic (2nd-order Taylor) approximation to the objective function in the neighborhood of the optimal wight-parameter of the unregularized objective \(\mathbf{w}^{\ast} = \arg \min_{\boldsymbol{w}} J(\boldsymbol{w})\).4

The approximation \(\hat{J}\):$$\hat{J}(\boldsymbol{\theta})=J\left(\boldsymbol{w}^{\ast}\right)+\frac{1}{2}\left(\boldsymbol{w}-\boldsymbol{w}^{\ast}\right)^{\top} \boldsymbol{H}(J(\boldsymbol{w}^{\ast}))\left(\boldsymbol{w}-\boldsymbol{w}^{\ast}\right) \tag{7.6}$$

where \(\boldsymbol{H}\) is the Hessian matrix of \(J\) with respect to \(\mathbf{w}\) evaluated at \(\mathbf{w}^{\ast}\).

Notice:

- There is no first-order term in this quadratic approximation, because \(\boldsymbol{w}^{\ast}\) is defined to be a minimum, where the gradient vanishes.

- Because \(\boldsymbol{w}^{\ast}\) is the location of a minimum of \(J\), we can conclude that \(\boldsymbol{H}\) is positive semidefinite.

The gradient of \(\hat{J} + \Omega(\mathbf{\theta})\):

$$\nabla_{\boldsymbol{w}} \hat{J}(\boldsymbol{w})=\boldsymbol{H}(J(\boldsymbol{w}^{\ast}))\left(\tilde{\boldsymbol{w}}-\boldsymbol{w}^{\ast}\right) + \alpha \tilde{\boldsymbol{w}} \tag{7.7}$$

And the minimum is achieved at \(\nabla_{\boldsymbol{w}} \hat{J}(\boldsymbol{w}) = 0\):

$$\tilde{\boldsymbol{w}}=(\boldsymbol{H}+\alpha \boldsymbol{I})^{-1} \boldsymbol{H} \boldsymbol{w}^{\ast} \tag{7.10}$$

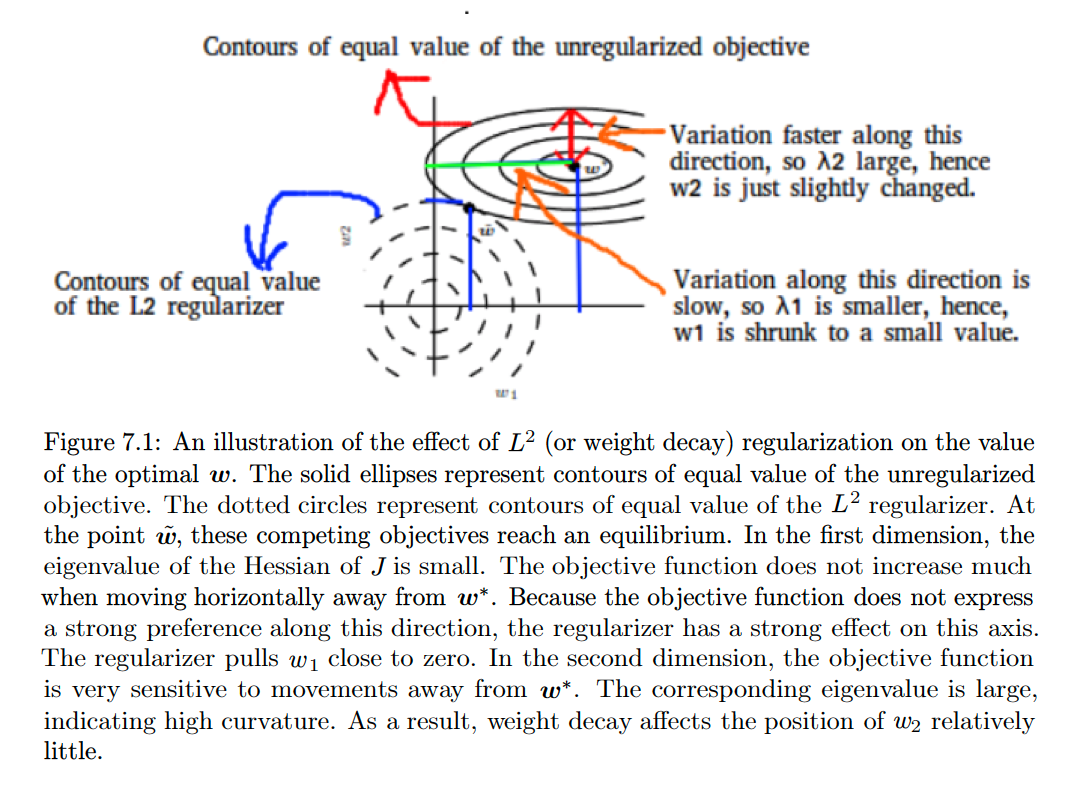

Effects:

- As \(\alpha\) approaches \(0\): the regularized solution \(\tilde{\boldsymbol{w}}\) approaches \(\boldsymbol{w}^{\ast}\).

- As \(\alpha\) grows: we apply spectral decomposition to the real and symmetric \(\boldsymbol{H} = \boldsymbol{Q} \boldsymbol{\Lambda} \boldsymbol{Q}^{\top}\):

$$\begin{aligned} \tilde{\boldsymbol{w}} &=\left(\boldsymbol{Q} \mathbf{\Lambda} \boldsymbol{Q}^{\top}+\alpha \boldsymbol{I}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{Q} \boldsymbol{\Lambda} \boldsymbol{Q}^{\top} \boldsymbol{w}^{\ast} \\ &=\left[\boldsymbol{Q}(\boldsymbol{\Lambda}+\alpha \boldsymbol{I}) \boldsymbol{Q}^{\top}\right]^{-1} \boldsymbol{Q} \boldsymbol{\Lambda} \boldsymbol{Q}^{\top} \boldsymbol{w}^{\ast} \\ &=\boldsymbol{Q}(\boldsymbol{\Lambda}+\alpha \boldsymbol{I})^{-1} \boldsymbol{\Lambda} \boldsymbol{Q}^{\top} \boldsymbol{w}^{\ast} \end{aligned} \tag{7.13}$$

Thus, we see that the effect of weight decay is to rescale \(\boldsymbol{w}^{\ast}\) along the axes defined by the eigenvector of \(\boldsymbol{H}\). Specifically, the component of \(\boldsymbol{w}^{\ast}\) that is aligned with the \(i\)-th eigenvector of \(\boldsymbol{H}\) is rescaled by a factor of \(\frac{\lambda_{i}}{\lambda_{i}+\alpha}\).

Summary:

Condition Effect of Regularization \(\lambda_{i}>>\alpha\) Not much \(\lambda_{i}<<\alpha\) The weight value almost shrunk to \(0\) - Applying \(L^2\) regularization to Linear Regression :

-

- Weight Decay Analysis (blog)

\(L^2\) Regularization Derivation:

\(L^2\) regularization is equivalent to MAP Bayesian inference with a Gaussian prior on the weights.The MAP Estimate:

$$\begin{aligned} \hat{\theta}_ {\mathrm{MAP}} &=\arg \max_{\theta} P(\theta \vert y) \\ &=\arg \max_{\theta} \frac{P(y \vert \theta) P(\theta)}{P(y)} \\ &=\arg \max_{\theta} P(y \vert \theta) P(\theta) \\ &=\arg \max_{\theta} \log (P(y \vert \theta) P(\theta)) \\ &=\arg \max_{\theta} \log P(y \vert \theta)+\log P(\theta) \end{aligned}$$

We place a Gaussian Prior on the weights, with zero mean and equal variance \(\tau^2\):

$$\begin{aligned} \hat{\theta}_ {\mathrm{MAP}} &=\arg \max_{\theta} \log P(y \vert \theta)+\log P(\theta) \\ &=\arg \max _{\boldsymbol{w}}\left[\log \prod_{i=1}^{n} \dfrac{1}{\sigma \sqrt{2 \pi}} e^{-\dfrac{\left(y_{i}-\boldsymbol{w}^{\top}\boldsymbol{x}_i\right)^{2}}{2 \sigma^{2}}}+\log \prod_{j=0}^{p} \dfrac{1}{\tau \sqrt{2 \pi}} e^{-\dfrac{w_{j}^{2}}{2 \tau^{2}}} \right] \\ &=\arg \max _{\boldsymbol{w}} \left[-\sum_{i=1}^{n} \dfrac{\left(y_{i}-\boldsymbol{w}^{\top}\boldsymbol{x}_i\right)^{2}}{2 \sigma^{2}}-\sum_{j=0}^{p} \dfrac{w_{j}^{2}}{2 \tau^{2}}\right] \\ &=\arg \min_{\boldsymbol{w}} \dfrac{1}{2 \sigma^{2}}\left[\sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(y_{i}-\boldsymbol{w}^{\top}\boldsymbol{x}_i\right)^{2}+\dfrac{\sigma^{2}}{\tau^{2}} \sum_{j=0}^{p} w_{j}^{2}\right] \\ &=\arg \min_{\boldsymbol{w}} \left[\sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(y_{i}-\boldsymbol{w}^{\top}\boldsymbol{x}_i\right)^{2}+\lambda \sum_{j=0}^{p} w_{j}^{2}\right] \\ &= \arg \min_{\boldsymbol{w}} \left[ \|XW - \boldsymbol{y}\|^2 + \lambda {\|\boldsymbol{w}\|_ 2}^2\right]\end{aligned}$$

Properties:

- Notice that L2-regularization has a rotational invariance. This actually makes it more sensitive to irrelevant features. [Ref]

- Adding L2-regularization to a convex function gives a strongly-convex function. So L2-regularization can make gradient descent converge much faster. (^ same ref)

Notes:

- L2-reg and Adversarial Examples (New Angle)

- Weight Decay Analysis (blog)

- Interpreting the Penalty term \(\lambda\):

In the Bayesian Interpretation of Weight Decay; by assuming a Gaussian Distribution on the errors:

the Penalty term \(\lambda\) can be interpreted as the (squared) ratio of two variances of the data and the weights respectively: \(\lambda = \frac{\sigma_{D}^{2}}{\sigma_{W}^{2}}\). - A visual explanation for regularization of linear models (Blog)

- What happens in a Single Step:

- \(L^1\) Regularization:

\(L^1\) Regularization is another way to regulate the model by penalizing the size of its parameters; the technique adds a regularization term:$$\Omega(\boldsymbol{\theta})=\|\boldsymbol{w}\|_{1}=\sum_{i}\left|w_{i}\right| \tag{7.18}$$

which is a sum of absolute values of the individual parameters.

The regularized objective function is given by:

$$\tilde{J}(\boldsymbol{w} ; \boldsymbol{X}, \boldsymbol{y})=\alpha\|\boldsymbol{w}\|_ {1}+J(\boldsymbol{w} ; \boldsymbol{X}, \boldsymbol{y}) \tag{7.19}$$

with the corresponding (sub) gradient:

$$\nabla_{\boldsymbol{w}} \tilde{J}(\boldsymbol{w} ; \boldsymbol{X}, \boldsymbol{y})=\alpha \operatorname{sign}(\boldsymbol{w})+\nabla_{\boldsymbol{w}} J(\boldsymbol{X}, \boldsymbol{y} ; \boldsymbol{w}) \tag{7.20}$$

Notice that the regularization contribution to the gradient, no longer scales linearly with each \(w_i\); instead it is a constant factor with a sign = \(\text{sign}(w_i)\).

[Analysis]

Sparsity of the \(L^1\) regularization:

In comparison to \(L^2\), \(L^1\) regularization results in a solution that is more sparse.

The sparsity property has been used extensively as a feature selection mechanism.- LASSO: The Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator integrates an \(L^1\) penalty with a linear model and a least-squares cost function.

The \(L^1\) penalty causes a subset of the weights to become zero, suggesting that the corresponding features may safely be discarded.

\(L^1\) Regularization Derivation:

\(L^1\) regularization is equivalent to (the log-prior term in) MAP Bayesian inference with an isotropic Laplace distribution prior on the weights:$$\log p(\boldsymbol{w})=\sum_{i} \log \operatorname{Laplace}\left(w_{i} ; 0, \frac{1}{\alpha}\right)=-\alpha\|\boldsymbol{w}\|_ {1}+n \log \alpha-n \log 2 \tag{7.24}$$

note that we can ignore the terms \(\log \alpha-\log 2\) because they do not depend on \(\boldsymbol{w}\).

$$\begin{aligned} \hat{\theta}_ {\mathrm{MAP}} &=\arg \max_{\theta} \log P(y \vert \theta)+\log P(\theta) \\ &=\arg \max _{\boldsymbol{w}}\left[\log \prod_{i=1}^{n} \dfrac{1}{\sigma \sqrt{2 \pi}} e^{-\dfrac{\left(y_{i}-\boldsymbol{w}^{\top}\boldsymbol{x}_i\right)^{2}}{2 \sigma^{2}}}+\log \prod_{j=0}^{p} \dfrac{1}{2 b} e^{-\dfrac{\left|\theta_{j}\right|}{2 b}} \right] \\ &=\arg \max _{\boldsymbol{w}} \left[-\sum_{i=1}^{n} \dfrac{\left(y_{i}-\boldsymbol{w}^{\top}\boldsymbol{x}_i\right)^{2}}{2 \sigma^{2}}-\sum_{j=0}^{p} \dfrac{\left|w_{j}\right|}{2 b}\right] \\ &=\arg \min_{\boldsymbol{w}} \dfrac{1}{2 \sigma^{2}}\left[\sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(y_{i}-\boldsymbol{w}^{\top}\boldsymbol{x}_i\right)^{2}+\dfrac{\sigma^{2}}{b} \sum_{j=0}^{p}\left|w_{j}\right|\right] \\ &=\arg \min_{\boldsymbol{w}} \left[\sum_{i=1}^{n}\left(y_{i}-\boldsymbol{w}^{\top}\boldsymbol{x}_i\right)^{2}+\lambda \sum_{j=0}^{p}\left|w_{j}\right|\right] \\ &= \arg \min_{\boldsymbol{w}} \left[ \|XW - \boldsymbol{y}\|^2 + \lambda \|\boldsymbol{w}\|_ 1\right]\end{aligned}$$

Properties:

- \(L^1\) regularization can occasionally produce non-unique solutions. A simple example is provided in the figure when the space of possible solutions lies on a 45 degree line.

- LASSO: The Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator integrates an \(L^1\) penalty with a linear model and a least-squares cost function.

-

\(L^1\) VS \(L^2\) Regularization:

- Feature Correlation and Sparsity:

- Identical features:

- \(L^1\) regularization spreads weight arbitrarily (all weights same sign)

- \(L^2\) regularization spreads weight evenly

- Linearly related features:

- \(L^1\) regularization chooses variable with larger scale, \(0\) weight to others

- \(L^2\) prefers variables with larger scale — spreads weight proportional to scale

- Identical features:

Interpreting Sparsity with an Example:

Let’s imagine we are estimating two coefficients in a regression. In \(L^2\) regularization, the solution \(\boldsymbol{w} =(0,1)\) has the same weight as \(\boldsymbol{w}=(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}, \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}})\) so they are both treated equally. In \(L^1\) regularization, the same two solutions favor the sparse one:$$\|(1,0)\|_{1}=1<\left\|\left(\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}, \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\right)\right\|_{1}=\sqrt{2}$$

So \(L^2\) regularization doesn’t have any specific built in mechanisms to favor zeroed out coefficients, while \(L^1\) regularization actually favors these sparser solutions.

- Feature Correlation and Sparsity:

Notes:

- Elastic Net Regularization:

$$\Omega = \lambda\left(\alpha\|w\|_{1}+(1-\alpha)\|w\|_{2}^{2}\right), \alpha \in[0,1]$$

- Combines both \(L^1\) and \(L^2\)

- Used to produce sparse solutions, but to avoid the problem of \(L^1\) solutions being sometimes Non-Unique

- The problem mainly arises with correlated features

- Elastic net regularization tends to have a grouping effect, where correlated input features are assigned equal weights.

Advanced Regularization Techniques

-

Regularization and Under-Constrained Problems:

In some cases, regularization is necessary for machine learning problems to be properly define.Many linear models (e.g. Linear Regression, PCA) depend on inverting \(\boldsymbol{X}^{\top}\boldsymbol{X}\). This is not possible if \(\boldsymbol{X}^{\top}\boldsymbol{X}\) is singular. In this case, many forms of regularization correspond to solving inverting \(\boldsymbol{X}^{\top} \boldsymbol{X}+\alpha \boldsymbol{I}\) instead. This regularized matrix is guaranteed to be invertible.

- \(\boldsymbol{X}^{\top}\boldsymbol{X}\) can be singular if:

- The data-generating function truly has no variance in some direction.

- No Variance is observed in some direction because there are fewer examples (rows of \(\boldsymbol{X}\)) than input features (columns).

Models with no closed-form solution can, also, be underdetermined:

Take logistic regression on a linearly separable dataset, if a weight vector \(\boldsymbol{w}\) is able to achieve perfect classification, then so does \(2\boldsymbol{w}\) but with even higher likelihood. Thus, an iterative optimization procedure (sgd) will continually increase the magnitude of \(\boldsymbol{w}\) and, in theory, will never halt.

We can use regularization to guarantee the convergence of iterative methods applied to underdetermined problems: e.g. weight decay will cause gradient descent to quit increasing the magnitude of the weights when the slope of the likelihood is equal to the weight decay coefficient.Linear Algebra Perspective:

Given that the Moore-Penrose pseudoinverse \(\boldsymbol{X}^{+}\) of a matrix \(\boldsymbol{X}\) can solve underdetermined linear equations:$$\boldsymbol{X}^{+}=\lim_{\alpha \searrow 0}\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\top} \boldsymbol{X}+\alpha \boldsymbol{I}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{X}^{\top} \tag{7.29}$$

we can now recognize the equation as performing linear regression with weight-decay.

Specifically, \(7.29\) is the limit of eq \(7.17\) as the regularization coefficient shrinks to zero.$$\boldsymbol{w}=\left(\boldsymbol{X}^{\top} \boldsymbol{X}+\alpha \boldsymbol{I}\right)^{-1} \boldsymbol{X}^{\top} \boldsymbol{y} \tag{7.17}$$

We can thus interpret the pseudoinverse as stabilizing underdetermined problems using regularization.

The Pseudoinverse:

When applied to underdetermined systems w/ non-unique solutions; It finds the minimum norm solution to a linear system.

This “OLS” solution implies that not all linear functions are the same for OLS. It restricts the space of all possible non-unique linear functions that satisfy the equation to a subset of minimal norm.

From SLT perspective, the pseudoinverse introduces bias towards certain solutions.

- \(\boldsymbol{X}^{\top}\boldsymbol{X}\) can be singular if:

- Dataset Augmentation:

Having more data is the most desirable thing to improving a machine learning model’s performance. In many cases, it is relatively easy to artificially generate data.- Applications: for certain problems like classification this approach is readily usable. E.g. for a classification task, we require the model to be invariant to certain types of transformations, of which we can generate data by applying them on our current dataset.

The most successful application of data-augmentation has been in object recognition. - Non-Applicable: this approach is not applicable to many problems, especially those that require us to learn the true data-distribution first E.g. Density Estimation.

Noise Injection as Data-Augmentation:

Injecting noise in the input to a NN (Siestma and Dow, 1991) can also be seen as a form of data augmentation.- Motivation:

- For many classification and (some) regression tasks: the task should be possible to solve even if small random noise is added to the input (Local Constancy)

- Moreover, NNs prove not to be very robust to noise.

Injecting Noise in the Hidden Units:

It can be seen as doing data-augmentation at multiple levels of abstraction. This approach can be highly effective provided that the magnitude of the noise is carefully tuned (Poole et al. 2014).Dropout can be seen as a process of constructing new inputs by multiplying by noise.

- Applications: for certain problems like classification this approach is readily usable. E.g. for a classification task, we require the model to be invariant to certain types of transformations, of which we can generate data by applying them on our current dataset.

- Noise Robustness:

We can apply Noise Injection to different components of the model as a way to regularize the model:

Injecting Noise in the Input Layer:- Motivation:

We have motivated the injection of noise, to the inputs, as a dataset augmentation strategy. - Interpretation:

For some models, the addition of noise with infinitesimal variance at the input of the model is equivalent to imposing a penalty on the norm of the weights (Bishop, 1995a,b).

Injecting Noise in the Hidden Layers:

- Motivation:

We can motivate it as a variation of data augmentation. - Interpretation:

It can be seen as doing data-augmentation at multiple levels of abstraction. - Applications:

The most successful application of this type of noise injection is Dropout.

It can be seen as a process of constructing new inputs by multiplying by noise.

Injecting Noise in the Weight Matrices:

- Interpretation:

- It can be interpreted as a stochastic implementation of Bayesian inference over the weights.

- The Bayesian View:

The Bayesian treatment of learning would consider the model weights to be uncertain and representable via a probability distribution that reflects this uncertainty. Adding noise to the weights is a practical, stochastic way to reflect this uncertainty.

- The Bayesian View:

- It can, also, be interpreted as equivalent a more traditional form of regularization, encouraging stability of the function to be learned.

-

- It can be interpreted as a stochastic implementation of Bayesian inference over the weights.

- Applications:

This technique has been used primarily in the context of recurrent neural networks (Jim et al., 1996; Graves, 2011).

Injecting Noise in the Output Layer:

- Motivation:

- Most datasets have some number of mistakes in the \(y\) labels. It can be harmful to maximize \(\log p(y \vert \boldsymbol{x})\) when \(y\) is a mistake. One way to prevent this is to explicitly model the noise on the labels.

One can assume that for some small constant \(\epsilon\), the training set label \(y\) is correct with probability \(1-\epsilon\).

This assumption is easy to incorporate into the cost function analytically, rather than by explicitly drawing noise samples (e.g. label smoothing). - MLE with a softmax classifier and hard targets may never converge - the softmax can never predict a probability of exactly \(0\) or \(1\), so it will continue to learn larger and larger weights, making more extreme predictions forever.{: #bodyContents33mle}

- Most datasets have some number of mistakes in the \(y\) labels. It can be harmful to maximize \(\log p(y \vert \boldsymbol{x})\) when \(y\) is a mistake. One way to prevent this is to explicitly model the noise on the labels.

- Interpretation:

For some models, the addition of noise with infinitesimal variance at the input of the - Applications:

Label Smoothing regularizes a model based on a softmax with \(k\) output values by replacing the hard \(0\) and \(1\) classification targets with targets of \(\dfrac{\epsilon}{k-1}\) and \(1-\epsilon\), respectively.- Applied to MLE problem: Label smoothing, compared to weight-decay, has the advantage of preventing the pursuit of hard probabilities without discouraging correct classification.

- Application in modern NN: (Szegedy et al. 2015)

Notes:

- Motivation:

-

Semi-Supervised Learning:

Semi-Supervised Learning is a class of ML tasks and techniques that makes use of both unlabeled examples from \(P(\mathbf{x})\) and labeled examples from \(P(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y})\) to estimate \(P(\mathbf{y} \vert \mathbf{x})\) or predict \(\mathbf{y}\) from \(\mathbf{x}\).In the context of Deep Learning, Semi-Supervised Learning usually refers to learning a representation \(\boldsymbol{h}=f(\boldsymbol{x})\); the goal being to learn a representation such that examples from the same class have similar representations.

Usually, Unsupervised Learning provides us clues (e.g. clustering) that influence the representation of the data.PCA, as a preprocessing step before applying a classifier, is a long-standing variant of this approach.

Approach:

Instead of separating the supervised and unsupervised criteria, we can instead have a generative model of \(P(\mathbf{x})\) (or \(P(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y})\)) which shares parameters with a discriminative model \(P(\mathbf{y} \vert \mathbf{x})\).

The idea is to share the unsupervised/generative criterion with the supervised criterion to express a prior belief that the structure of \(P(\mathbf{x})\) (or \(P(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{y})\)) is connected to the structure of \(P(\mathbf{y} \vert \mathbf{x})\), which is captured by the shared parameters.

By controlling how much of the generative criterion is included in the total criterion, one can find a better trade-off than with a purely generative or a purely discriminative training criterion (Lasserre et al., 2006; Larochelle and Bengio, 2008). -

Multitask Learning:

Multitask Learning is a way to improve generalization by pooling the examples (which can be seen as soft constraints imposed on the parameters) arising out of several tasks. In the same way that additional data put more pressure on the parameters of the model toward values that generalize well, when part of a model is shared across tasks, that part of the model is more constrained toward good values (assuming the sharing is justified), often yielding better generalization.Improved generalization due to improved statistical strength of the shared parameters (in proportion w/ increased # of examples). This happens only is some assumptions about the statistical relationship of the different tasks are valid; i.e. they share something.

From the point of view of deep learning, the underlying prior belief is the following:

Among the factors that explain the variations observed in the data associated with the different tasks, some are shared across two or more tasks.Types:

- Task-specific: These parameters benefit only from that particular task for generalization.

These are the later layers in the NN. - Generic, (shared across all tasks): benefit from the pooled data of all the tasks.

These are the earlier layers in the NN.

- Task-specific: These parameters benefit only from that particular task for generalization.

-

Early Stopping:

Early Stopping: is a regularization method that aims to obtain a model with better validation set error (\(\implies\) generalization) by saving the model parameters at every epoch and returning to the parameter setting at the point in time with the lowest validation set error.Premise of Early Stopping:

For a model with high representational capacity, after a certain point of time during training, the training error continues to decrease but the validation error begins to increase (overfitting). In such a scenario, a better idea would be to return back to the point where the validation error was the least.

Algorithm:

Early stopping requires the use of a validation set. Thus, we are not using the entire dataset for training. Choosing the ideal number of steps before we stop training can be done with cross-validation. Then, to utilize the entire dataset, a second phase of training can be done where the complete training set is used. There are two choices here:- Train from scratch for the same number of steps as in the Early Stopping case.

- Use the weights learned from the first phase of training and continue training using the complete data (not as well behaved).

As Regularization:

Early Stopping affects the optimization procedure by restricting it to a small volume of the parameter space, in the neighbourhood of the initial parameter value \(\boldsymbol{\theta}_ {O}\).

Let \(\tau\) be the number of optimization steps taken (\(\tau\) training iterations) with lr \(\epsilon\). The product \(\epsilon\tau\) can be seen as a measure of effective capacity. Assuming the gradient is bounded, restricting both the number of iterations and the learning rate limits the volume of parameter space reachable from \(\boldsymbol{\theta}_ {O}\); thus, \(\epsilon\tau\) behaves as the reciprocal of the regularization coefficient for weight decay: \(\epsilon\tau \approx \dfrac{1}{\lambda}\) \(\implies\)

The number of training iterations has a role inversely proportional to the weight decay coefficient:$$\tau \approx \dfrac{1}{\epsilon\lambda}$$

- When the number of iterations \(\tau\) is small \(\iff \lambda\) is large: Regularization is large and the capacity is small

- When the number of iterations \(\tau\) is large \(\iff \lambda\) is small: Regularization is small and the capacity is large

Parameter values corresponding to directions of significant curvature (of the objective function) are regularized less than directions of less curvature. Of course, in the context of early stopping, this really means that parameters that correspond to directions of significant curvature tend to learn early relative to parameters corresponding to directions of less curvature.

Equivalence to Weight Decay for Linear Models:

To compare with classical \(L^{2}\) regularization, we examine a simple setting where the only parameters are linear weights \((\boldsymbol{\theta}=\boldsymbol{w})\). We can model the cost function \(J\) with a quadratic approximation in the neighborhood of the empirically optimal value of the weights \(\boldsymbol{w}^{ * }\):$$\hat{J}(\boldsymbol{\theta})=J\left(\boldsymbol{w}^{ * }\right)+\frac{1}{2}\left(\boldsymbol{w}-\boldsymbol{w}^{ * }\right)^{\top} \boldsymbol{H}\left(\boldsymbol{w}-\boldsymbol{w}^{ * }\right)$$

where \(\boldsymbol{H}\) is the Hessian matrix of \(J\) with respect to \(\boldsymbol{w}\) evaluated at \(\boldsymbol{w}^{ * } .\) Given the assumption that \(\boldsymbol{w}^{ * }\) is a minimum of \(J(\boldsymbol{w}),\) we know that \(\boldsymbol{H}\) is positive semidefinite.

Properties:

- Early stopping is an unobtrusive form of regularization, in that it requires almost no change in the underlying training procedure, the objective function, or the set of allowable parameter values:

- This means that it is easy to use early stopping without damaging the learning dynamics. This is in contrast to weight decay, where one must be careful not to use too much weight decay and trap the network in a bad local minimum corresponding to a solution with pathologically small weights.

- Early Stopping does not add any extra hyperparameters, making it easy to incorporate without the need for extra tuning.

- It reduces the computation cost of training by:

- Lowering the number of training steps

- Regularizing the model without having to add additional penalty terms (computation of gradients of additional terms)

- Early stopping may be used either alone or in conjunction with other regularization strategies. Even when using regularization strategies that modify the objective function to encourage better generalization, it is rare for the best generalization to occur at a local minimum of the training objective.

- It is a form of spectral regularization

- ON EARLY STOPPING IN GRADIENT DESCENT LEARNING (paper)

Intuition:

(1) One way to think of early stopping is as a very efficient hyperparameter selection algorithm. In this view, the number of training steps is just another hyperparameter. We can see that this hyperparameter has a \(U\)-shaped validation set performance curve. Most hyperparameters that control model capacity have such a \(U\)-shaped validation set performance curve. In the case of early stopping, we are controlling the effective capacity of the model by determining how many steps it can take to fit the training set.(2) Early stopping can be viewed as regularization in time. Intuitively, a training procedure like gradient descent will tend to learn more and more complex functions as the number of iterations increases. By regularizing on time, the complexity of the model can be controlled, improving generalization.

(3) With a bounded step size, the number of steps dictates the radius ball (around your initial point) of points that is reachable. By stopping early, you limit this radius. “Weight decay is equivalent to a Lagrangian relaxation of a constraint on the weight norm. Early stopping (by previous argument) gives you the same constraint (assuming you start from 0). If you don’t start from 0, you might be able to still use triangle inequality to prove it.”

Notes:

- Why small weights in NN lead to lower capacity:

For sigmoid activation, when the weights are very small, every hidden unit is in its linear range.

So a net with a large layer of hidden units has no more capacity than a linear net in which inputs are directly connected to the outputs.

This implies that the effective number of parameters is \(N\) minus the number of hidden unit parameters.

Thus, we can think of Early Stopping as controlling the effective number of parameters in the model by allowing it to use more of them until it fits the right amount of patterns in the data. (hinton Lec 9a) - A Continuous-Time View of Early Stopping for Least Squares (or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Early Stopping) (blog!)

- No Free Lunch for Early Stopping (paper)

Shows that with a uniform prior on models having the same training error, early stopping at some fixed training error above the training error minimum results in an increase in the expected generalization error.

-

Parameter Tying and Parameter Sharing:

Unlike the the methods focused on bringing the weights to a fixed point, e.g. 0 in the case of norm penalty, there might be situations where we might have some prior knowledge on the kind of dependencies that the model should encode.Parameter Tying:

If two tasks are similar enough (similar input/output distributions), we might want to have the parameters of both models be close to each other in value. We do this with Parameter Tying: to use regularization to have two sets of parameters close to each other.

One way to achieve that (in an application) is to regularize the parameters of one model (\(L^2\) norm), trained as a classifier in a supervised paradigm, to be close to the parameters of another model, trained in an unsupervised paradigm (to capture the distribution of the observed input data).5Parameter Sharing:

The more popular way is Parameter Sharing: to use constraints, to force sets of parameters to be equal.A significant advantage of parameter sharing over regularizing the parameters to be close (via a norm penalty) is that only a subset of the parameters (the unique set) needs to be stored in memory, e.g. in CNNs this can lead to significant reduction in the memory footprint of the model.

Parameter sharing has enabled CNNs to dramatically lower the number of unique model parameters and to significantly increase network sizes without requiring a corresponding increase in training data.

- Sparse Representations:

Another strategy is to place a penalty on the activations of the units in a neural network, encouraging their activations to be sparse. This indirectly imposes a complicated penalty on the model parameters.Unlike Weight decay which acts by placing a penalty directly on the model parameters.

\(L^1\) regularization induces sparse parametrization i.e. sparse weights.

Representational sparsity, on the other hand, induces sparse representations i.e. describes a representation where many of the elements of the representation are zero (or close to zero).Norm penalty regularization of representations is performed by adding to the loss function $J$ a norm penalty on the representation. This penalty is denoted \(\Omega(\boldsymbol{h}) .\) As before, we denote the regularized loss function by \(\tilde{J}\):

$$\tilde{J}(\boldsymbol{\theta} ; \boldsymbol{X}, \boldsymbol{y})=J(\boldsymbol{\theta} ; \boldsymbol{X}, \boldsymbol{y})+\alpha \Omega(\boldsymbol{h})$$

where \(\alpha \in[0, \infty)\) weights the relative contribution of the norm penalty term, with larger values of \(\alpha\) corresponding to more regularization.

The regularizer \(\Omega\):

- \(L^1\) norm can be used

- Penalty derived from a Student $t$ prior distribution on the representation

- KL-divergence penalties: especially useful for representations with elements constrained to lie on the unit interval

Other approaches obtain representational sparsity with a hard constraint on the activation values. For example, orthogonal matching pursuit (OMP) (Pati et al, 1993) encodes an input \(x\) with the representation \(h\) that solves the constrained optimization problem:

$$\underset{\boldsymbol{h},\|\boldsymbol{h}\|_ {0}< k}{\arg \min }\|\boldsymbol{x}-\boldsymbol{W} \boldsymbol{h}\|^{2}$$

where \(\|\boldsymbol{h}\|_ {0}\) is the number of nonzero entries of \(\boldsymbol{h}\) . This problem can be solved efficiently when \(\boldsymbol{W}\) is constrained to be orthogonal. This method is often called OMP-\(k\), with the value of \(k\) specified to indicate the number of nonzero features allowed. Coates and \(\mathrm{Ng}(2011)\) demonstrated that \(\mathrm{OMP}-1\) can be a very effective feature extractor for deep architectures.

-

Ensemble Learning:

Ensemble Learning is a set of ensemble methods that use multiple learning algorithms, (models) and a strategy called model averaging to combine the outcomes of those model, to obtain better predictive performance.Model averaging is an extremely powerful and reliable method for reducing generalization error.

Motivation:

The reason that model averaging works is that different models will usually not make all the same errors on the test set.

Consider for example a set of \(k\) regression models. Suppose that each model makes an error \(\epsilon_{i}\) on each example, with the errors drawn from a zero-mean multivariate normal distribution with variances \(\mathbb{E}\left[\epsilon_{i}^{2}\right]=v\) and covariances \(\mathbb{E}\left[\epsilon_{i} \epsilon_{j}\right]=c\). Then the error made by the average prediction of all the ensemble models is \(\frac{1}{k} \sum_{i} \epsilon_{i}\). The expected squared error of the ensemble predictor is:$$\begin{aligned} \mathbb{E}\left[\left(\frac{1}{k} \sum_{i} \epsilon_{i}\right)^{2}\right] &=\frac{1}{k^{2}} \mathbb{E}\left[\sum_{i}\left(\epsilon_{i}^{2}+\sum_{j \neq i} \epsilon_{i} \epsilon_{j}\right)\right] \\ &=\frac{1}{k} v+\frac{k-1}{k} c \end{aligned}$$

- When the errors are perfectly correlated \(c=v\): the MSE reduces to \(v\), so the model averaging does not help at all.

- When the errors are perfectly uncorrelated \(c=0\), the expected squared error of the ensemble is only \(\dfrac{1}{k} v\).

Thus, the expected squared error of the ensemble is inversely proportional to the ensemble size.

In other words, on average, the ensemble will perform at least as well as any of its members, and if the members make independent errors, the ensemble will perform significantly better than its members.

As Regularization:

Regularization has two general definitions:

(1) Any modification we make to a learning algorithm that is intended to reduce its generalization error but not its training error.

(2) Regularization is a (more general) way of controlling a models capacity by allowing us to express preference for one function over another in the same hypothesis space; instead of including or excluding members from the hypothesis space completely.From those perspectives, the analysis (motivation) above shows that ensemble methods satisfy both criteria in gold.

Bagging:

Bagging is an ensemble method that aims to reduce the generalization error.

It reduces variance which corresponds to generalization error, thus decreasing capacity.Boosting:

Not all techniques for constructing ensembles are designed to make the ensemble more regularized than the individual models. For example, a technique called boosting (Freund and Schapire, 1996b,a) constructs an ensemble with higher capacity than the individual models.

It reduces bias which corresponds to approximation error, thus increasing capacity.

-

Dropout:

Dropout (Srivastava et al., 2014) provides a computationally inexpensive but powerful method of regularizing a broad family of models.Dropout as (an approximation to) Bagging Ensemble Method for Neural Networks:

To a first approximation, dropout can be thought of as a method of making bagging practical for ensembles of very many large neural networks.

Bagging involves training multiple models and evaluating multiple models on each test example. This seems impractical when each model is a large neural network, since training and evaluating such networks is costly in terms of runtime and memory. It is common to use ensembles of five to ten neural networks—Szegedy et al. (2014a) used six to win the ILSVRC— but more than this rapidly becomes unwieldy.

Dropout provides an inexpensive approximation to training and evaluating a bagged ensemble of exponentially many neural networks. Specifically, dropout trains the ensemble consisting of all subnetworks that can be formed by removing nonoutput units from an underlying base network. In modern NNs, we can remove a unit by “multiplying” its output by zero.Recall that to learn with bagging, we define \(k\) different models, construct \(k\) different datasets by sampling from the training set with replacement, and then train model \(i\) on dataset \(i\). Dropout aims to approximate this process, but with an exponentially large number of neural networks.

Dropout Algorithm:

To train with dropout, we:- Use a minibatch-based learning algorithm that makes small steps, such as stochastic gradient descent.

- Each time we load an example into a minibatch, we randomly sample a different binary mask to apply to all the input and hidden units in the network.

- The mask for each unit is sampled independently from all the others.

- The probability of sampling a mask value of one (causing a unit to be included) is a hyperparameter fixed before training begins. It is not a function of the current value of the model parameters or the input example.

- Typically, an input unit is included with probability \(0.8\), and a hidden unit is included with probability \(0.5\).

- We then run forward propagation, back-propagation, and the learning update as usual.

Formally, suppose that a mask vector \(\mu\) specifies which units to include, and \(J(\boldsymbol{\theta}, \boldsymbol{\mu})\) defines the cost of the model defined by parameters \(\boldsymbol{\theta}\) and mask \(\boldsymbol{\mu}\) Then dropout training consists of minimizing \(\mathbb{E}_ {\boldsymbol{\mu}} J(\boldsymbol{\theta}, \boldsymbol{\mu})\). The expectation contains exponentially many terms, but we can obtain an unbiased estimate of its gradient by sampling values of \(\boldsymbol{\mu}\).

Differences:

- Training (compare each number):

- Bagging:

- The models are all independent.

- Each model is trained to convergence on its respective training set.

- Dropout:

- The models share parameters, with each model inheriting a different subset of parameters from the parent neural network.

This parameter sharing makes it possible to represent an exponential number of models with a tractable amount of memory. - Most models are not explicitly trained at all—usually, the model is large enough that it would be infeasible to sample all possible subnetworks within the lifetime of the universe. Instead, a tiny fraction of the possible subnetworks are each trained for a single step, and the parameter sharing causes the remaining subnetworks to arrive at good settings of the parameters.

- The models share parameters, with each model inheriting a different subset of parameters from the parent neural network.

Beyond these difference, dropout follows the bagging algorithm; e.g. training set encountered by each subnetwork is indeed a subset of the original training set sampled with replacement.

- Bagging:

- Inference (Prediction):

So far, our description of bagging and dropout has not required that the model be explicitly probabilistic. Now, we assume that the model’s role is to output a probability distribution.- Bagging: Each model \(i\) produces a probability distribution \(p^{(i)}(y \vert \boldsymbol{x})\).

The prediction of the ensemble is given by the arithmetic mean of all these distributions:$$\frac{1}{k} \sum_{i=1}^{k} p^{(i)}(y \vert \boldsymbol{x})$$

- Dropout: Each submodel defined by mask vector \(\boldsymbol{\mu}\) defines a probability distribution \(p(y \vert x, \mu)\).

The arithmetic mean over all masks is given by:$$\sum_{\mu} p(\boldsymbol{\mu}) p(y \vert \boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{\mu})$$

where \(p(\boldsymbol{\mu})\) is the probability distribution that was used to sample \(\boldsymbol{\mu}\) at training time.

- Issues with direct inference with the arithmetic mean:

Because this sum includes an exponential number of terms, it is intractable to evaluate except when the structure of the model permits some form of simplification. - Solution - Geometric Mean + Weight Scaling Inference:

The following approach allows us to obtain a good approximation to the predictions of the entire ensemble, at the cost of only one forward propagation.

The geometric mean of multiple probability distributions is not guaranteed to be a probability distribution. We guarantee it by imposing the requirement that none of the submodels assigns probability \(0\) to any event, and we renormalize the resulting distribution.

The Unnormalized distribution defined by the geometric mean:$$\tilde{p}_{\text {ensemble }}(y \vert \boldsymbol{x})=2 \sqrt[2 d]{\prod_{\boldsymbol{\mu}} p(y \vert \boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{\mu})}$$

where \(d\) is the number of units that may be dropped6.

The Normalized distribution:$$p_{\text {ensemble }}(y \vert \boldsymbol{x})=\frac{\tilde{p}_{\text {ensemble }}(y \vert \boldsymbol{x})}{\sum_y \tilde{p}_{\text {ensemble }}\left(y^{\prime} \vert \boldsymbol{x}\right)}$$

Weight Scaling Inference Rule: that approximates \(p_{\text {ensemble}}\) by evaluating \(p(y \vert \boldsymbol{x})\) in one model: the model with all units, but with the weights going out of unit \(i\) multiplied by the probability of including unit \(i\).

- Analysis and Justification:

- Warde-Farley et al. (2014) present arguments and empirical evidence that the geometric mean performs comparably to the arithmetic mean in this context.

- A key insight (Hinton et al., 2012c) involved in dropout is that we can approximate \(p_{\text {ensemble}}\) by evaluating \(p(y \vert \boldsymbol{x})\) in one model: the model with all units, but with the weights going out of unit \(i\) multiplied by the probability of including unit \(i\) - The Weight Scaling Inference Rule:. The motivation for this modification is to capture the right expected value of the output from that unit.

There is not yet any theoretical argument for the accuracy of this approximate inference rule in deep nonlinear networks, but empirically it performs very well.

The goal is to make sure that the expected total input to a unit at test time is roughly the same as the expected total input to that unit at train time.

is a method that aims to make sure that the expected total input to a unit at test time is roughly the same as the expected total input to that unit at train time.

For many classes of models that do not have nonlinear hidden units, the weight scaling inference rule is exact; e.g. softmax regression classifier (proof page 260 dlbook).

The weight scaling rule is also exact in other settings, including regression networks with conditionally normal outputs as well as deep networks that have hidden layers without nonlinearities.

However, the weight scaling rule is only an approximation for deep models that have nonlinearities. Though the approximation has not been theoretically characterized, it often works well, empirically.

Goodfellow et al. (2013a) found experimentally that the weight scaling approximation can work better (in terms of classification accuracy) than Monte Carlo approximations to the ensemble predictor. This held true even when the Monte Carlo approximation was allowed to sample up to 1,000 subnetworks. Gal and Ghahramani (2015) found that some models obtain better classification accuracy using twenty samples and the Monte Carlo approximation.

It appears that the optimal choice of inference approximation is problem dependent.- One other, non-efficient, way to do inference is to approximate it with sampling by averaging together the output from many masks. Even 10–20 masks are often sufficient to obtain good performance.

Weight Scaling Rule is far superior.

- One other, non-efficient, way to do inference is to approximate it with sampling by averaging together the output from many masks. Even 10–20 masks are often sufficient to obtain good performance.

- Analysis and Justification:

- Issues with direct inference with the arithmetic mean:

- Bagging: Each model \(i\) produces a probability distribution \(p^{(i)}(y \vert \boldsymbol{x})\).

Properties and Advantages:

- Srivastava et al. (2014) showed that dropout is more effective than other standard computationally inexpensive regularizers, such as weight decay, filter norm constraints, and sparse activity regularization.

- Dropout may be combined with other forms of regularization to yield a further improvement.

- Dropout is very computationally cheap.

Using it in training requires only \(\mathcal{O}(n)\) computation per example per update, to generate \(n\) random binary numbers and multiply them by the state. - Dropout does not significantly limit the type of model or training procedure that can be used.

It works well with nearly any model that uses a distributed representation and can be trained with stochastic gradient descent; e.g. feedforward neural networks, probabilistic models such as restricted Boltzmann machines, and RNNs. - Stochasticity is Neither necessary Nor sufficient for the regularization effects of dropout:

- The stochasticity used while training with dropout is NOT necessary for the approaches success. It is just a means of approximating the sum over all submodels.

Fast Dropout is an analytical approximations to this marginalization. - Applying the same stochastic masks in a method analogous to boosting, where the stochastically sampled ensemble members are not trained independently, show almost no regularization effect compared to when the ensemble members are trained to perform well independently of each other.

Dropout boosting is one method that trains the entire ensemble to jointly maximize the log-likelihood on the training set; and experiments have shown that it displays no regularization compared to training the entire network as a single model.

- The stochasticity used while training with dropout is NOT necessary for the approaches success. It is just a means of approximating the sum over all submodels.

- The sharing of the weights means that every model is very strongly regularized.

This regularization is much better than L2 or L1 penalties since instead of pulling the weights towards zero, we are pulling the weights towards the correct value of the weights. - Dropout - Hinton

- Running the stochastic model several times on the same input (instead of all the weights halved), gives an idea of the uncertainty in the answer.

- We can use dropout in the input layer, but with a higher probability of keeping an input unit:

Denoising Autoencoders use this.

Practical Disadvantages/Issues:

- Typically the optimal validation set error is much lower when using dropout, but this comes at the cost of a much larger model and many more iterations of the training algorithm. For very large datasets, regularization confers little reduction in generalization error. In these cases, the computational cost of using dropout and larger models may outweigh the benefit of regularization.

- When extremely few labeled training examples are available, dropout is less effective. Bayesian neural networks (Neal, 1996) outperform dropout on the Alternative Splicing Dataset (Xiong et al., 2011), where fewer than 5,000 examples are available (Srivastava et al., 2014). When additional unlabeled data is available, unsupervised feature learning can gain an advantage over dropout.

Dropout as Regularization - Effectiveness of Dropout:

- Dropout can be viewed as a means of performing efficient, approximate bagging.

- Dropout trains not just a bagged ensemble of models, but an ensemble of models that share hidden units.

This means each hidden unit must be able to perform well regardless of which other hidden units are in the model. Hidden units must be prepared to be swapped and interchanged between models.

Dropout, thus, regularizes each hidden unit to be not merely a good feature but a feature that is good in many contexts.

This prevents Co-Adaptation between hidden-units on the Training Data. - A large portion of the power of dropout arises from the fact that the masking noise is applied to the hidden units. This can be seen as a form of highly intelligent, adaptive destruction of the information content of the input rather than destruction of the raw values of the input.

This views dropout as noise-injection in the hidden units. Which can be seen as doing data-augmentation at multiple levels of abstraction.

For example, if the model learns a hidden unit that detects a face by finding the \(h_i\) nose, then dropping corresponds to erasing the information that there is a nose \(h_i\) in the image. The model must learn another \(h_i\), that either redundantly encodes the presence of a nose or detects the face by another feature, such as the mouth. Traditional noise injection techniques that add unstructured noise at the input are not able to randomly erase the information about a nose from an image of a face unless the magnitude of the noise is so great that nearly all the information in the image is removed. Destroying extracted features rather than original values allows the destruction process to make use of all the knowledge about the input distribution that the model has acquired so far. - When viewed as noise-injection, an important aspect of dropouts success is that it uses multiplicative noise.

Multiplicative noise does not allow for pathological solutions to the noise robustness problem: If the noise were additive with fixed scale, then a rectified linear hidden unit \(h_{i}\) with added noise \(\epsilon\) could simply learn to have \(h_{i}\) become very large in order to make the added noise \(\epsilon\) insignificant by comparison.

Dropout and Batch Normalization:

Another deep learning algorithm, batch normalization, reparametrizes the model in a way that introduces both additive and multiplicative noise on the hidden units at training time. The primary purpose of batch normalization is to improve optimization, but the noise can have a regularizing effect, and sometimes makes dropout unnecessary.Modifying Dropout and source of Regularization:

One of the key insights of dropout is that training a network with stochastic behavior and making predictions by averaging over multiple stochastic decisions implements a form of bagging with parameter sharing.

Earlier, we described dropout as bagging an ensemble of models formed by including or excluding units. Yet this model averaging strategy does not need to be based on inclusion and exclusion. In principle, any kind of random modification is admissible.

In practice, we must choose modification families that:

(1) neural networks are able to learn to resist.

(2) Ideally, we should also use model families that allow a fast approximate inference rule.

We can think of any form of modification parametrized by a vector \(\mu\) as training an ensemble consisting of \(p(y \vert \boldsymbol{x}, \boldsymbol{\mu})\) for all possible values of \(\boldsymbol{\mu}\) There is no requirement that \(\boldsymbol{\mu}\) have a finite number of values. For example, \(\boldsymbol{\mu}\) can be real valued. Srivastava et al. \((2014)\) showed that multiplying the weights by \(\boldsymbol{\mu} \sim \mathcal{N}(\mathbf{1}, I)\) can outperform dropout based on binary masks. Because \(\mathbb{E}[\boldsymbol{\mu}]=\mathbf{1}\), the standard network automatically implements approximate inference in the ensemble, without needing any weight scaling.Dropout as Weight Decay in linear models:

Wager et al. (2013) showed that, when applied to linear regression, dropout is equivalent to L2 weight decay, with a different weight decay coefficient for each input feature. The magnitude of each feature’s weight decay coefficient is determined by its variance. Similar results hold for other linear models.

For deep models, dropout is NOT equivalent to weight decay.

Notes:

-

Adversarial Training:

Adversarial training refers to training on examples that are adversarially generated and it has been shown to reduce the error rate.Adversarial Examples: are examples that are intentionally constructed by using an optimization procedure to search for an input \(\boldsymbol{x}^{\prime}\) near a data point \(\boldsymbol{x}\) such that the model output is very different at \(\boldsymbol{x}^{\prime} .\) In many cases, \(\boldsymbol{x}^{\prime}\) can be so similar to \(\boldsymbol{x}\) that a human observer cannot tell the difference between the original example and the adversarial example, but the network can make highly different predictions.

Szegedy et al. (2014b) found that even neural networks that perform at human level accuracy have a nearly \(100\%\) error rate on adversarial examples.

Application in Regularization:

Adversarial Examples are interesting in the context of regularization because one can reduce the error rate on the original test set via adversarial training—training on adversarially perturbed examples from the training set (Szegedy et al., 2014b; Goodfellow et al., 2014b).

Goodfellow et al. (2014b) showed that one of the primary causes of these adversarial examples is excessive linearity. Neural networks are built out of primarily linear building blocks. In some experiments the overall function they implement proves to be highly linear as a result. These linear functions are easy to optimize. Unfortunately, the value of a linear function can change very rapidly if it has numerous inputs. If we change each input by \(\epsilon\) , then a linear function with weights \(w\) can change by as much as \(\epsilon \|w\|_ 1\), which can be a very large amount if \(w\) is high-dimensional.

Adversarial training discourages this highly sensitive locally linear behavior by encouraging the network to be locally constant in the neighborhood of the training data. This can be seen as a way of explicitly introducing a local constancy prior into supervised neural nets.As Semi-supervised Learning:

Virtual Adversarial Examples are adversarial examples generated using not the true label but a label provided by a trained model (Miyato et al., 2015).

Using virtual examples, we can train a classifier to assign the same label to \(x\) and \(x^{\prime}\). This encourages the classifier to learn a function that is robust to small changes anywhere along the manifold where the unlabeled data lie. The assumption motivating this approach is that different classes usually lie on disconnected manifolds, and a small perturbation should not be able to jump from one class manifold to another class manifold.At a point \(\boldsymbol{x}\) that is not associated with a label in the dataset, the model itself assigns some label \(\hat{y}\) . The model’s label \(\hat{y}\) may not be the true label, but if the model is high quality, then \(\hat{y}\) has a high probability of providing the true label. We can seek an adversarial example \(\boldsymbol{x}^{\prime}\) that causes the classifier to output a label \(y^{\prime}\) with \(y^{\prime} \neq \hat{y}\).

Motivation:

The assumption motivating this approach is that different classes usually lie on disconnected manifolds, and a small perturbation should not be able to jump from one class manifold to another class manifold.

-

Tangent Distance, Tangent Prop and Manifold Tangent Classifiers:

Tangent Distance Algorithm:

Many ML models assume the data to lie on a low dimensional manifold to overcome the curse of dimensionality. The inherent assumption which follows is that small perturbations that cause the data to move along the manifold (it originally belonged to), shouldn’t lead to different class predictions. The idea of the tangent distance algorithm to find the K-nearest neighbors using the distance metric as the distance between manifolds. A manifold \(M_i\) is approximated by the tangent plane at \(x_i\), hence, this technique needs tangent vectors to be specified.Tangent Prop Algorithm:

The tangent prop algorithm proposed to learn a neural network based classifier, \(f(x)\), which is invariant to known transformations causing the input to move along its manifold. Local invariance would require that \(\bigtriangledown_x f(x)\) is perpendicular to the tangent vectors \(V^{(i)}\). This can also be achieved by adding a penalty term that minimizes the directional directive of \(f(x)\) along each of the \(V(i)\):$$\Omega(f)=\sum_{i}\left(\left(\nabla_{\boldsymbol{x}} f(\boldsymbol{x})\right)^{\top} \boldsymbol{v}^{(i)}\right)^{2}$$

Tangent Propagation is similar to data augmentation in that both of them use prior knowledge of the domain to specify various transformations that the model should be invariant to. However, tangent prop only resists infinitesimal perturbations while data augmentation causes invariance to much larger perturbations.

Drawbacks:

While this analytical approach is intellectually elegant, it has two major drawbacks.- It only regularizes the model to resist infinitesimal perturbation.

Explicit dataset augmentation confers resistance to larger perturbations. - The infinitesimal approach poses difficulties for models based on rectified linear units.

These models can only shrink their derivatives by turning units off or shrinking their weights. They are not able to shrink their derivatives by saturating at a high value with large weights, as sigmoid or tanh units can.

Dataset augmentation works well with rectified linear units because different subsets of rectified units can activate for different transformed versions of each original input.

Manifold Tangent Classifier:

The manifold tangent classifier (Rifai et al., 2011c), eliminates the need to know the tangent vectors a priori. Autoencoders can estimate the manifold tangent vectors.Manifold Tangent Classifier works in two parts:

- Use Autoencoders to learn the manifold structures using Unsupervised Learning.

- Use these learned manifolds with tangent prop.

- It only regularizes the model to resist infinitesimal perturbation.

Notes:

- A practical rule for choosing a regularizer:

- Stochastic noise is “high frequency”

- Deterministic noise is also non-smooth

Thus, we should constrain learning towards smoother hypotheses. I.E. fit the signal more than you fit the noise (which is non-smooth). We end up harming both, but harming the irregular, non-smooth noise more.

- Regularization does two things - reduce fit to noise AND reduce overfitting:

- Regularization Recommendations (Practical):

- You should always consider using regularization, unless you have a very large dataset, e.g. big-data scale.

“Unless your training set contains tens of millions of examples or more, you should include some mild forms of regularization from the start.”

— Page 426, Deep Learning, 2016. - A good general recommendation is to design a neural network structure that is under-constrained and to use regularization to reduce the likelihood of overfitting.

“… controlling the complexity of the model is not a simple matter of finding the model of the right size, with the right number of parameters. Instead, … in practical deep learning scenarios, we almost always do find—that the best fitting model (in the sense of minimizing generalization error) is a large model that has been regularized appropriately.”

— Page 229, Deep Learning, 2016. - Early stopping should almost universally be used in addition to a method to keep weights small during training.

“Early stopping should be used almost universally.”

— Page 426, Deep Learning, 2016. - Some more specific recommendations include:

These recommendations would suit Multilayer Perceptrons and Convolutional Neural Networks.- Classical: use early stopping and weight decay (L2 weight regularization).

- Alternate: use early stopping and added noise with a weight constraint.

- Modern: use early stopping and dropout, in addition to a weight constraint.

- Some recommendations for RNNs include:

- Classical: use early stopping with added weight noise and a weight constraint such as maximum norm.

- Modern: use early stopping with a backpropagation-through-time-aware version of dropout and a weight constraint.

- You should always consider using regularization, unless you have a very large dataset, e.g. big-data scale.

-

Where we (Hadamard) define Well-Posed Problems as having the properties (1) A Solution Exists (2) It is Unique (3) It’s behavior changes continuously with the initial conditions. ↩

-

So, you can think of the NFL theorems as providing some kind of theoretical justification for regularization or theoretical understanding that helps us see what the role of regularization is and provides some partial explanation for the empirical observation that it seems to often be effective. ↩

-

More generally, we could regularize the parameters to be near any specific point in space and, surprisingly, still get a regularization effect, but better results will be obtained for a value closer to the true one, with zero being a default value that makes sense when we do not know if the correct value should be positive or negative. ↩

-

The approximation is perfect if the objective function is truly quadratic, as in the case of linear regression w/ MSE. ↩

-

The architectures were constructed such that many of the parameters in the classifier model could be paired to corresponding parameters in the unsupervised model. ↩

-

Here we use a uniform distribution over \(\mu\) to simplify the presentation, but nonuniform distributions are also possible. ↩